Temperance - Learning From A Legend

“Most powerful is he who has himself in his own power.” – Seneca.

Temperance (or self-discipline) is the ability to keep your lower self in check and strengthen your higher self. It involves working hard, practicing good habits, enduring challenges, setting boundaries, and turning a blind eye to temptations. In short, it’s about living a life guided by principles, moderation, and determination.

For me, for much of my life, it has been, Hell, no. Not for me. Self-discipline? More like self-deprivation! Maybe you celebrate or even envy people who take the easy path. You might think they’re having more fun or getting ahead faster. But look more closely, and you’ll realize that all that glitters isn’t gold. Take greed, for instance. It means you’re always on the prowl for more – and so never really enjoy everything you currently have. And not realizing your full potential? That’s a state which breeds pain, misery, and self-loathing.

Self-discipline isn’t about depriving yourself – in fact, it’s the opposite. It’s about using control to open a world of opportunity.

It’s true that it takes courage to cultivate self-discipline. But embracing this lifestyle will likely make you more successful. And, more importantly, it’ll make you great – no matter what happens.

-------------------------

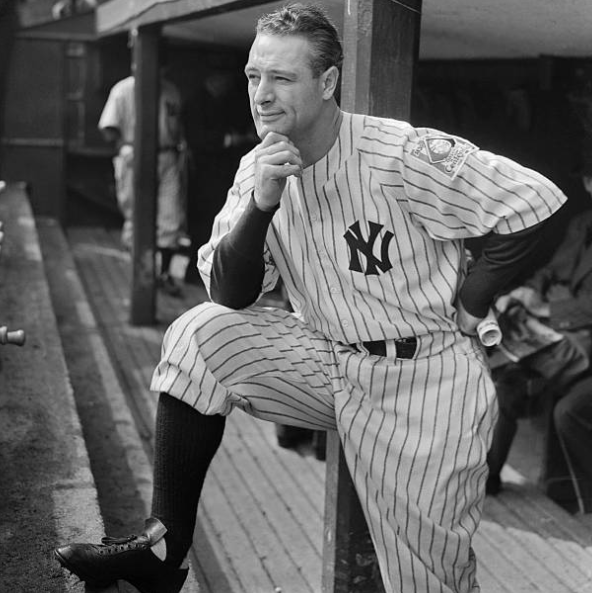

He played through fevers and migraines. He played through crippling back pain; pulled muscles; sprained ankles; and once, the day after being hit in the head by an 80 mph fastball, he suited up and played in Babe Ruth's hat, because the swelling made it impossible to put on his own.

For 2,130 consecutive games, Lou Gehrig played first base for the New York Yankees, a streak of physical stamina that stood for the next five-and-a-half decades. It was a feat of human endurance so long immortalized that it's easy to miss how incredible it actually was. The Major League Baseball (MLB) regular season in those days was 152 games. Gehrig's Yankees went deep in the postseason, nearly every year, reaching the World Series a remarkable seven times.

For 17 years, Gehrig played from April to October, without rest, at the highest level imaginable. In the off-season, players barnstormed and played in exhibition games, sometimes traveling as far away as Japan to do so. During his time with the Yankees, Gehrig played some 350 doubleheaders and traveled at least 200,000 miles across the country, mostly by train and bus.

Yet he never missed a game.

Not because he was never injured or sick, but because he was an Iron Horse of a man who refused to quit, who pushed through pain and physical limits that others would have used as an excuse. At some point, Gehrig's hands were X-rayed, and stunned doctors found at least 17 healed fractures. Over the course of his career, he'd broken nearly every one of his fingers-and it not only hadn't slowed him down, but he'd failed to say a word about it. In another sense, he's almost unfairly famous for the streak, which overshadows the stats he accumulated along the way.

His career batting average was an unbelievable .340, which he topped only when it counted, hitting .361 in his postseason career. (In two different World Series, he batted over .500.) He hit 495 home runs, including 23 grand slams - a record that stood for more than seven decades. In 1934, he became just the 3rd player ever to win the MLB Triple Crown, leading the league in batting average, home runs, and RBIs (runs batted in). He's 6th all-time with 1,995 RBIs, making him, effectively, one of the greatest teammates in the history of the game. He was a two-time MVP, seven-time All-Star, six-time World Series Champion, Hall of Famer, and the first player ever to have his number retired.

While the streak started in earnest in June 1925, when Gehrig replaced Wally Pipp, a Yankees legend, in reality, his Herculean endurance could be seen at an early age. Born to German immigrants in New York in 1903, Gehrig was the only one of four children to survive infancy.

He entered the world a whopping 14 pounds, and his mother's German cooking seems to have plumped him up from there. It was the teasing of school kids that first hardened the determination of the young boy, sending him to his father's turnverein, a German gymnastics club where Gehrig began to develop the powerful lower body that later drove in so many runs.

Not naturally coordinated, a boyhood friend once joked that Gehrig's body often "behaved as if it were drunk." He wasn't born an athlete. He made himself one in the gym.

Life as a poor immigrant was not easy. Gehrig's father was a drinker, and a bit of a lazy man. It's more than ironic to read of his father's chronic excuses and sick days. This example shamed Gehrig, inspiring him to turn dependability and toughness into nonnegotiable assets (in a bit of foreshadowing, he never missed a day of school). Thankfully, his mother not only supported him, but she also provided an incredible example of a quiet, indefatigable work ethic as well. She worked as a cook. She worked as a laundress. She worked as a baker. She worked as a cleaning lady, hoping to provide her son a ticket to a better life.

But the poverty, the poverty was always there. "No one who went to school with Lou," a classmate recalled, "can forget the cold winter days and Lou coming to school wearing a khaki shirt, khaki pants and heavy brown shoes, but no overcoat, nor any hat." He was a poor boy, a fate no one would choose, but it did shape him.

So it went with Gehrig, who, even as his Yankees salary made him one of the highest-paid athletes in America, was rarely seen in a hat or even a vest in New York winters. Only later, when he married a kind and loving woman, could he be convinced to put on a coat, for her sake.

Most kids like to play sports. Lou Gehrig saw in the game a higher calling. Baseball was a profession that demanded control of, as well as care for, the body-since it was both the obstacle and the vehicle for success.

Gehrig did both.

He worked harder than anyone. "Fitness was almost a religion to him," one teammate would say of him. "I am a slave to baseball," Gehrig said. A willing slave, a slave who loved the job and remained forever grateful at just the opportunity to play.

This kind of dedication pays dividends. When Gehrig stepped up to the plate, he was communing with something divine. He stood, serenely, in a heavy wool uniform that no player today could perform in. He would sway, trading weight between his feet, settling into his batting stance. When he swung at a pitch, it was his enormous legs that did the work-sending the ball off his bat, deep, deep, out of the ballpark.

Some batters have a sweet spot; Gehrig could hit anywhere, off anyone. And when he did? He ran. For a guy who was teased for having "piano legs," it's pretty remarkable that Gehrig stole home plate more than a dozen times in his career. He wasn't all power. He was speed too. Hustle. Finesse.

There were players with more talent, with more personality, with more brilliance; but nobody outworked him, nobody cared more about conditioning, and nobody loved the game more.

When you love the work, you don't cheat it or the demands it asks of you. You respect even the most trivial aspects of the pursuit-he never threw his bat, or even flipped it. One of the only times he ever got in trouble with management was when they found out he was playing stickball in the streets of his old neighborhood with local kids, sometimes even after Yankees games. He just couldn't pass up the opportunity to play . . .

Still, there must have been so many days when he wasn't feeling it. When he wanted to quit. When he doubted himself. When it felt like he could barely move. When he was frustrated and tired of his own high standards. Gehrig was not superhuman. He had the same voice in his head that all of us do. He just cultivated the strength, made a habit, of not listening to it. Because once you start compromising, well, now you're compromised . . .

"I have the will to play," he said. "Baseball is hard work and the strain is tremendous. Sure, it's pleasurable, but it's tough." You'd think that everyone has that will to play, but of course, that's not true. Some of us get by on natural talent, hoping never to be tested. Others are dedicated up to a point, but they'll quit if it gets too hard. That was true then, as it is now, even at the elite level. A manager in Gehrig's time described it as an "age of explanations" everyone was ready with an excuse. There was always a reason why they couldn't give their best, didn't have to hold the line, were showing up to camp less than prepared.

As a rookie, Joe DiMaggio once asked Gehrig who he thought was going to pitch for the opposing team, hoping perhaps, to hear it was someone easy to hit. "Never worry about that, Joe," Gehrig explained. "Just remember they always save the best for the Yankees."

And by extension, he expected every member of the Yankees to bring their best with them too. That was the deal: To whom much is given, much is expected. The obligation of a champion is to act like a champion . . . while working as hard as somebody with something to prove.

Gehrig wasn't a drinker. He didn't chase girls or thrills or drive fast cars. He was no "good-time Charlie," he'd often say. At the same time, he made it clear, "I'm not a preacher and I'm not a saint." His biographer wrote of Gehrig that the man's "clean living did not grow out of a smugness and prudery, a desire for personal sanctification. He had a stubborn, pushing ambition. He wanted something. He chose the most sensible and efficient route to getting it."

One doesn't take care of the body because to abuse it is a sin, but because if we abuse the temple, we insult our chances of success as much as any god. Gehrig was fully ready to admit that his discipline meant he missed out on a few pleasures. He also knew that those who live the fast or the easy life miss something too-they fail to fully realize their own potential. Discipline isn't deprivation…it brings rewards.

Still, Gehrig could have easily gone in a different direction. In the midst of an early career slump while playing in the minor leagues, Gehrig went out one night with some teammates and got so drunk that he was still boozed up at first pitch the next day. Somehow, he didn't just manage to play, but he played better than he had in months. He found, miraculously, that the nerves, the overthinking, had disappeared with a few nips from a bottle between innings.

It was a seasoned coach who noticed and sat Gehrig down. He'd seen this before. He knew the short-term benefits of the shortcut. He understood the need for release and for pleasure too. But he explained the long-term costs, and he spelled out the future Gehrig could expect if he didn't develop more sustainable coping mechanisms. That was the end of it, we're told, and "not because of any prissy notions of righteousness that it was evil or wrong to take a drink but because he had a driving, non-stop ambition to become a great and successful ball player. Anything that interfered with that ambition was poison to him."

It meant something to him to be a ballplayer, to be a Yankee, to be a first-generation American, to be someone who kids looked up to.

Gehrig, as it happened, continued to live with his parents for his first ten seasons, often taking the subway to the stadium. More than financially comfortable, he later owned a small house in New Rochelle. To Gehrig, money was at best a tool, at worst a temptation. As the Yankees reigned over the game, the team was treated to an upgraded dugout, with padded seats replacing the old Spartan bench. Gehrig was spotted by the team's manager tearing off a section. "I get tired of sitting on cushions," he said of the posh life of an athlete in his prime. "Cushions in my car, cushions on the chairs at home-every place I got they have cushions."

He knew that getting comfortable was the enemy, and that success is an endless series of invitations to get comfortable. It's easy to be disciplined when you have nothing. What about when you have everything? What about when you're so talented that you can get away with not giving everything?

The thing about Lou Gehrig is that he chose to be in control. This wasn't discipline enforced from above or by the team. His temperance was an interior force, emanating from deep within his soul. He chose it, despite the sacrifices, despite the fact that others allowed themselves to forgo such penance and got away with it. Despite the fact that it usually wasn't recognized - not until long after he was gone anyway.

Did you know that immediately after Ruth's legendary "called" home run that Lou Gehrig hit one too? Without any dramatic gestures either. Actually, it was his second of the game. Or that they have the same number of league batting titles? Or that Ruth struck out almost twice as many times as Gehrig?

Lou not only kept his body in check in a way that Ruth didn't (Ruth ballooned to 240 pounds), but Gehrig checked his ego too. He was, a reporter would write, "unspoiled, without the remotest vestige of ego, vanity or conceit." The team always came first. Before even his own health. Let the headlines go to whomever wanted them.

Gehrig could have chosen this path but then again, he could have never tolerated it. There was a time where his trainer once complained that if all ballplayers were like Gehrig there wouldn't be any job for trainers on ball clubs. Gehrig did his own prep, took care of his own training and just as religiously in the offseason. He rarely needed rub downs or rehab the only thing he asked of the staff was that a stick of gum be put out for him in his locker before games - two if they were going into a double header.

Without question, nobody plays that many games in a row without being a tough son of a bitch. During a game Cincinnati, a bad throw from his third baseman forced Gehrig to grab for the ball in the dirt where he jammed his thumb into the ground. In the dugout his teammate thought he'd be in for cursing out. “I think it's broken” was all Gehrig said. “I didn't hear a peep out of Lou”, his teammate recounted in amazement – “never a word of complaint about my rotten throw and what it did to his thumb”, and of course he was back in the lineup the following day.

“I guess the streak’s over”, a pitcher joked after knocking Gehrig unconscious with a pitch in June 1934. For five terrible minutes, Lou laid there unmoving, death being a real possibility in the era before helmets. He was rushed to the hospital and most expected he'd be out for two weeks even if the X-ray for a skull fracture came back negative. Again, he was back in the batter’s box the next day.

Still, you might have expected a hesitation or flinch when the next ball came hurtling towards him. That is why pitchers will bean in a batter from time to time because it makes them cautious - the pattern instinct for self-preservation causes them to step back in a game where a millimeter might make all the difference. Instead, Gehrig leaned in and hit a triple. A few innings later he hit another one. And before the game was rained out, he hit his third while recovering from a nearly fatal blow to the brain.

“A thing like that can't stop us Dutchman”, was his only postgame comment.

What propels a person to push themselves this way sometimes it's simply to remind the body who was in charge. “It's just that I had to prove myself right away”, he said I wanted to make sure that that big whack on my head hadn't made me gun shy the plate.

There's an old story about Gehrig’s first game with the Yankees when he started his streak, he was supposedly hit with the ball that day too. “Do you want us to take you out”, the manager asked. “Hell no!!” Garrett was said. “It's taken me three years to get into this game and it's gonna take more than a crack on the head to get me out. 17 years later something finally did take him out, and it was far more serious than a wild pitch.

For someone who had been masterful at keeping control of his body, it must have been bewildering to Gehrig when his body stopped responding as it always had. Slowly but noticeably his swing wasn't as fast. He struggled to pull on his mitt. He fell down while putting on a pair of pants. He dragged his feet when he walked. Yet his sheer will keep him together to a degree that few suspected anything was wrong. He was even fooling himself.

Just to offer a perspective Gehrig's schedule, in August 1938 the Yankees played 36 games in 35 days, 10 games were doubleheaders. In one case there were five consecutive games, traveling to five cities covering thousands of miles by train. He hit .329 with nine home runs and 38 RBI's. For an athlete to do this without missing a game, without missing an inning in their mid-30’s, it's impressive. But Lou Gehrig did it as the early stages of ALS ravaged his body, slowing his motor skills, weakening his muscles and cramping his hands and feet.

It would be nearly a full additional season before Gehrig’s body finally gave out. A streak had taken on a life of its own – kept going. Gehrig continued gutting out hits and runs despite the occasional but uncharacteristic error on the field. But a man who knows his body even as they pushed and pushed and pushed past their limitations also has to know when to stop.

“Joe”, he said to the Yankees manager on an ordinary mayday in 1939, “I always said that when I felt I couldn't help the team anymore I would take myself out of the lineup. I guess that time has come”.

“When do you wanna quit, Lou?” McCarthy replied as he hoped this day would never come. “Now”, Lou replied. “Put Babe Dahlgren in.”

What had changed after weeks of inconsistent play, Gehrig fielded a ground ball and made a solid out it – a play he'd made thousands of times in his career. His teammates celebrated like it was one of his series winning homers, and in that moment, Lou knew he was holding them back.

As the starting lineup was called over the loudspeakers to some 12,000 people in Detroit, the announcer was just as stunned. For the first time in 21,130 games Gehrig’s name was not to be called. Still the announcer couldn't help himself, “how about a hand for Lou Gehrig who played 21,130 games in a row before he benched himself today.” The crowd, which included a friend of Gehrig’s in town on business, the one and only Wally Pipp (who Gehrig had first replaced 14 years earlier) struggled to register what it meant.

The crowd broke out and sustained applause, Gehrig waved and retreated to the dugout. His teammates watched in silence as the Iron Horse broke down and wept.

You have to do your best while you still have a chance. Life is short and you never know when the game, when your body will be taken away from you. Don't waste it.

On July 4, 1939 Lou entered Yankee Stadium for the final time in uniform, stripped now of the muscles that had long served him. All that was left was the man himself, his courage and his self-mastery. The fatigue was unbearable as he tried to beg off speaking but the crowd chanted, “WE WANT LOU, WE WANT LOU!”. Lou struggling to hold himself up and the words would prove that when we master the lower self, we elevate ourselves to a higher plane.

“For the past two weeks you have been reading about a bad break”, he said as he tried to keep himself together, “yet today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth”.

But eventually this luck would run out as it does for all of us. “Death came to the erstwhile Iron Man at 10:10am,” the New York Times wrote in 1941.

Like Lou Gehrig, each of us are in a battle with our physical form. First, to master it and bring it to its full potential, second as we age and get sick, to arrest its decline to quite literally rest the life. How we choose to treat ourselves is a training ground and a proving ground for the mind and the soul. What are you willing to put up with? What can you do without? What would you put yourself through? What can you produce with it? You say you love what you do but where is your proof? What kind of streak do you have to show for it?

Most of us don't have millions of fans watching or millions of dollars incentivizing us. We don't have a coach, or a trainer monitor the daily progress. There is no fighting weight for our profession. This actually makes our jobs and our lives harder, because we have to be our own manager, our own master. We are responsible for our own conditioning. We have to monitor our own intake and decide our own standards. Temperance is not a particularly sexy word and hardly the most fun concept but it can lead to greatness. Temperance, like a tempered sword. Simplicity and modesty, fortitude and self-control. In all things except our determination and toughness, we owe it to ourselves, to our goals, to the game, to keep going to keep pushing to stay pure - to be tough to conquer our bodies before they conquer us.